Making Lemonade out of Mrs. Lemmon: An Interview with Caroline Schimmel

In the 2019 documentary The Booksellers, book collector Caroline Schimmel shares some of the responses she got when she began collecting books by women writers in the 1960s. “I would say [to book dealers], ‘Show me where your women are.’ And they would say they didn’t have any,” she explains. “But then I would come back with a stack of books, and they would say, ‘Ah! There they are.’”

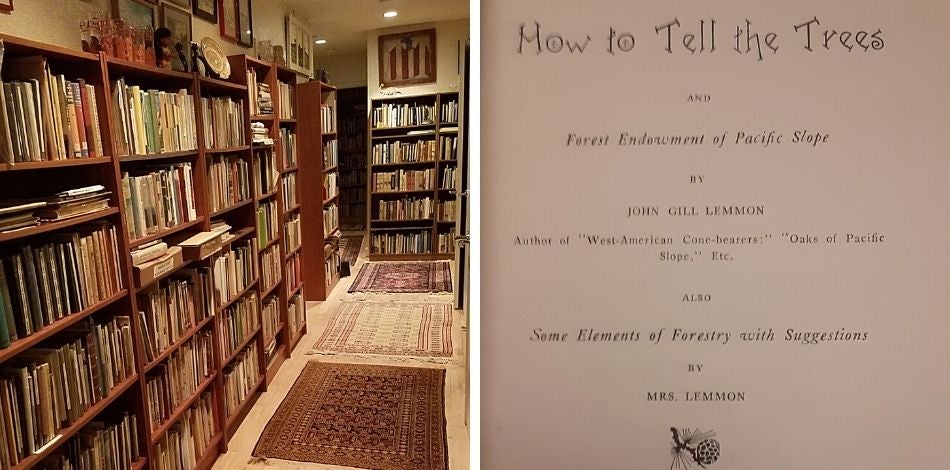

Today, Schimmel has amassed a collection of over 24,000 books and other objects, particularly art and textiles, that connect to the story of women in America. During a recent video tour of her New York home, she showed me Navajo blankets, family quilts from the 18th century, and a parka sewn by Inuit women for explorer Richard Evelyn Byrd. And, of course, she showed me her books, which cover nearly every visible surface. It’s remarkable to imagine that her collection was once even larger; in 2014, she donated more than 6,000 works to the University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Additional items from her collection went on display in the Penn Libraries’ Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts with the 2018 exhibit, “OK, I’ll Do It Myself: Narratives of Intrepid Women in the American Wilderness.”

“She was the first [book collector] to recognize the importance of collecting women talking about women,” says the Kislak Center’s Director of Special Collections Processing Regan Kladstrup, who appears in The Booksellers along with William Noel, who directed the Kislak Center during the period when the documentary was filmed. What does Schimmel see on the bookshelves of rare book dealers that her fellow bibliophiles did not? Why do these works by women writers appear invisible to so many people? The answer is simple, according to Schimmel: most people assume the author of a book is a man unless it is explicitly clear that the author is a woman. That means that when an author is credited with their initials, or uses a gender-neutral first name, or includes no first name at all, book collectors, dealers, and readers tend to assume that author is male. Taking her cue from the famous aphorism by Virginia Woolf, Schimmel works from the opposite assumption: if she is unsure about the gender of a book’s author, she hypothesizes that the author is a woman, and then conducts research to confirm her theory. Throughout our conversation, she reminded me of Woolf’s words again and again, “Anonymous was a woman!”

When I mentioned in passing that I had a personal research interest in the history of women in science, Schimmel immediately thought of a book to share with me. “I just discovered her last week,” she said. An examination of the cone-bearing trees of California published in 1902, the title page lists two authors: a Mr. John Gill Lemmon and his wife, credited merely as “Mrs. Lemmon.” “The title page alone says so much.” What was Mrs. Lemmon first name? What did she contribute to this slim scientific volume? Deepening the mystery further, “Mrs. Lemmon” is listed on the next page as the book’s sole copyright holder and the author of its dedication. Why? Not all book collectors would investigate the answers to such questions. Even historians have been known to ignore the female relatives listed as co-authors on the publications of the male scientists they study. But for Caroline Schimmel, the presence of Mrs. Lemmon is what makes the book worth having. She is hoping to do additional research to discover more about her.

This perspective on collecting women’s history affects the way Schimmel sees many kinds of artifacts and works of art. Remember the Richard Byrd parka? Most people would associate the artifact with the white male explorer, but for Schimmel, it tells the story of the anonymous Indigenous women who made it. It’s a visual reminder of their impact on history, not Byrd’s. “It’s so funny how you can look at an object in so many different ways. I bought my parka because of the stitchery, but somebody else would go, ‘Oh my God, that intrepid man, he wore that in the wilderness.’”

Has she ever put on the parka before? I was delighted to find out she had. She says that she once wore it to the annual meeting of the Explorer’s Club, the storied professional society of which Byrd had been a member. “Everyone had on even more over the top stuff, so hardly anybody even asked me what in the world I was doing, wearing that parka,” she laughed. “But it was so lightweight that I was comfortable, even though it was late spring.”

Caroline Schimmel’s efforts are one part of a larger project to make visible the stories of women who lurk just below the traditional historical record--women who wrote behind pseudonyms, or who collaborated anonymously with male relatives, or who contributed to larger scientific, political, or creative projects in ways that were deemed unsubstantial or unimportant until recently. Recent books and films like Hidden Figures and Ammonite have given popular audiences just a peek at the too-often-unseen role women have played in important historical efforts usually credited solely to men. Taking a more small-scale approach at the invisible contributions of women to history, novelist and English professor Bruce Holsinger made a splash on Twitter in 2017 when he began sharing excerpts from academic books in which male authors thanked their wives for typing--and more often than not, editing--their manuscripts. One such example reads, “I gratefully acknowledge my debt to my wife for typing the whole of this work at least twice, patiently deciphering my afterthoughts and insertions, and sternly correcting stylistic lapses.” His hashtag #ThanksForTyping has now inspired an edited volume, published just last month.

Schimmel is proud of the ways she has contributed to this larger project--of how, as she puts it, she has “made lemonade out of Mrs. Lemmon.” Though the book trade remains male-dominated, and collectors still tend to deem works by men more valuable than works by women, things are slowly changing. Over the years, Schimmel has developed a network of women book collectors who specialize in books by women, and booksellers increasingly recognize the importance of these collections as well. She remembers visiting a bookseller in Los Angeles early in her collecting career who claimed to have had no books by women on the shelves. As is her wont, Schimmel showed the dealer the women writers hiding in plain sight; when she visited again years later, the store had added a display dedicated to women authors. “It made my heart glow.”

Penn Libraries students, faculty, and staff can watch The Booksellers online through October 15, 2021. It is also available to anyone through a number of streaming services and other outlets. Learn more.

Date

March 31, 2021