“If You Don’t See the Book You Want on the Shelves, Write it.”

Checking in with the Penn Libraries Community Engagement Team

As this year draws to a close, Penn Libraries Community Engagement (PLCE) is taking a second to reflect on this last year. How can we continue working with our dynamic team of educators, librarians, University of Pennsylvania students, and community partners to ensure that all children have access to school libraries full of engaging, high quality, contemporary, and representative books? Since its inception in 2014, PLCE has been one of many groups working to address the literacy crisis and the de-prioritization and defunding of school libraries that have left the School District of Philadelphia with fewer than 7 librarians for over 200 public schools. Based on the belief that access to literacy programming opens minds, hearts, and worlds, and that libraries are forces for good in our society, we’ve expanded our mission in the past few years to include family literacy, storytelling programs, and events outside of our school library partners.

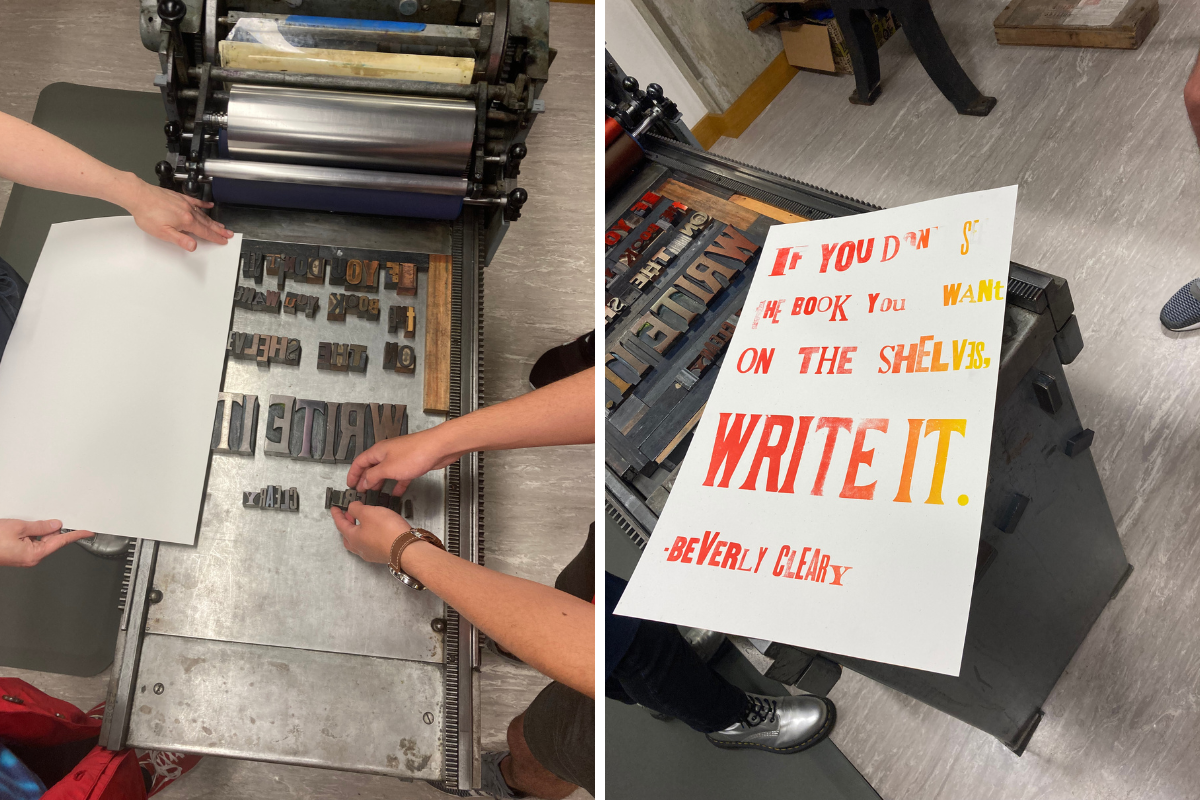

In June, to conclude our summer work-study students’ orientation, we walked from our offices in the Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center to the basement of the Fisher Fine Arts Library to visit the Common Press Studio. We’d decided to print posters for our Philadelphia Public School partner libraries that would not only look amazing, but also sum up how central finding yourself in books is to the work we do. We’d spent the day before poring over books for young readers, looking for a quote that could encapsulate how we feel about our work. We discussed the lenses we use to understand what we do. We dug into how important representation is, especially in picture books for young children. We considered the role libraries and librarians play in fostering spaces for everyone to tell their own stories, and how we, as readers, find stories that help to ground our experience and open our minds to new perspectives. Everyone has a rich and powerful story, but not everyone gets the opportunity to tell their story or have it read.

In light of this discussion, and of PLCE’s focus on school library collection development and storytelling, we decided to make a poster that featured a quote from Beverly Cleary: If you don’t see the book you want on the shelves, write it. We worked together, going through the trays of wood type at Common Press to find bold letters that, while not quite matching, worked together perfectly, and we printed our message in bright orange ink.

It’s this core belief that everyone has a story to tell, and that those rich and engaging stories belong on the shelves of our libraries to be read and loved and learned from, that motivates much of our work. In October, we partnered with Colorful Stories and Mt. Airy’s Lovett Library on an event for Reading Promise Week, a weeklong citywide celebration of youth literacy with events throughout Philadelphia, organized by Read by 4th. One shared goal was to ensure that storytelling and story creation was at the center of the event. We worked with local authors, illustrators, musicians, storytellers, and community members to help kids ages 3-8 write their own love letters to Philadelphia. On the night of October 12, around 100 people of all ages gathered on the lawn outside the library to celebrate literacy, build community, eat pizza, and add their story to their own shelves. For the entirety of the two-hour event, kids spent long periods at tables thoughtfully and carefully writing their stories with the help of local storytellers and illustrators. They left with beautiful handbound books that could be read again and again--tangible proof that their stories are important and belong on bookshelves.

In addition to storytelling initiatives, PLCE is working to ensure that book collections at partner schools empower students to tell their own stories! Before the COVD-19 pandemic, most of PLCE’s work took place in area elementary schools, where we helped students select books from the library and read aloud to classes. School libraries reopened in October and our Penn student team is once again working directly with young readers to explore all facets of literacy. As part of our effort to build collections at these schools, several members of our work-study student team read Abdul’s Story written by Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow and illustrated by Tiffany Rose. The book jacket describes Abdul, a young boy from Philly, as someone who “loves to tell stories. But writing them down is hard. His letters refuse to stay straight and face the right way. And despite all his attempts, his papers often wind up full of more eraser smudges than actual words. Abdul decides his stories just aren’t meant to be written down...until a special visitor comes to class and shows Abdul that even the best writers...make mistakes.”

Our work-study student team members read this book aloud, which they deemed emotional and beautiful, as practice for doing engaging read-a-louds for elementary school classes. We discussed what made the book successful with young people, pointing out the easy way of showing differences, via the illustrations, without creating an explicit narrative around them; for example, a student picked up on the fact that Abdul is left-handed and noted this “is such a subtle thing that isn’t good or bad, it just is.” The team sympathized with the fact that things were hard for Abdul, observing that he “felt left out because his life was not represented in the books he was reading.” Books like these and stories like Abdul’s are important not only because they empower us to tell our own stories, but also because they include the small realities of our lives. Abdul tells stories about the “bow-tie-wearing man hawking bean pies on Broad Street,” which our team loved because, “It highlights the small things that make you feel at home” and reminds us that our observations and realities are cherished and valuable.

As one student team member said, “Reading children’s books as an adult makes you feel like your story matters. If [Abdul’s Story] matters to me as an adult, I can’t imagine what it would mean to a kid.” In the beginning of the story, Abdul’s messy writing and pages with eraser marks torn into them are sources of shame for him, and this is something our student team could sympathize with. When Mr. Muhammad, a visiting writer, comes to class and shows Abdul his own messy notebook, Abdul starts to write his stories his own way: messy, expansive, and full of life, trusting they belong on the shelves. He begins to understand that his stories are bigger than just getting the letters right or the lines straight. Instead, as one student observed, “There’s not just one way to be a writer. What’s important is getting it out before refining it.” Another student added, “For someone who has a lot of stories in them, their hand does not move as quickly as their brain.”

We’re looking forward to another year of growing, learning, reading books, and telling stories. If you would like to help us get books like Abdul’s Story into our partner schools, please contact us at libcommeng@pobox.upenn.edu for information about how to get involved in our efforts.

Date

December 19, 2022