Nova khata: A Ukrainian Folk Art Journal in Interwar Galicia

The Penn Libraries has recently acquired several issues of the women’s journal Nova khata (New Home), which offer a unique window into Ukrainian culture as it existed a century ago.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it has become imperative for Westerners to understand the historical context of this region. With this in mind, the Penn Libraries has recently acquired several issues of the rare Ukrainian women’s journal Nova khata (New Home, 1925–39), which offer a unique window into Ukrainian culture as it existed a century ago in the western region of Ukraine called Galicia.

Galicia

Galicia (in Ukrainian: Halychyna) is an enigmatic land located at the heart of Europe, whose intricate history eludes modern understanding because it no longer exists as an independent entity. Nestled against the Carpathian Mountains at the boundary between Central and Eastern Europe, and centered around the significant city of Lviv (previously Lemberg or Lwów), the historical territory of Galicia is now divided between the present-day borders of western Ukraine and eastern Poland.

Historical Galicia began in medieval times, first as the Principality, then as the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia. At the height of its influence in the 13th century, Galicia-Volhynia served as an important center of multiple trade routes and the salt industry. After losing its independence in 1340, Galicia was variously controlled by large empires: the Kingdom of Poland, Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Imperial Russia, and Austria-Hungary. In the chaotic aftermath of World War I, Galicia ceased to exist, and became part of the Republic of Poland; after WWII this region was divided between Poland and the USSR until Ukraine gained its independence in 1991.[1]

Lviv and the Founding of Nova Khata

Nova khata was a monthly (sometimes semi-monthly) magazine, founded in Lviv (Lwów) in 1925 by women from the Ukrainske Narodnie Mystetstvo (Ukrainian Folk Art Cooperative), and published through 1939. The editors were Maria Gromnytska (1893–1978), Maria Furtak-Derkach (1896–1972), and Lidia Burachynska-Rudyk (1902–99), the latter a specialist in folk art who emigrated to Philadelphia in 1949 and became a leader of the Ukrainian diaspora.

|

|

At that time, Lviv (now in present-day Ukraine) was an Eastern outpost of the Polish Republic. Tarik Amar has noted that Lviv’s unique flavor grew from the ethnic diversity it had possessed since the 15th century. In 1900, Poles constituted about 1/2 of the city population, Jews 1/3, and Ukrainians about 1/5. As the most important city of historical Galicia (and its capital in the medieval era), Lviv was a locus of longings and nationalist aspirations, heightened by its position as a borderland city. As Omer Bartov and Eric Weitz have written, borderlands are “spaces-in-between,” where ethnicities intermingle, and distance from the seat of power turns these places into “ideological fantasies.” Lviv was always symbolically important to both the empires who controlled the region and those subjugated to that control, so that, while empires fought over it for centuries, it also became an important center for both Polish and Ukrainian nationalism.

Nova khata thus embodies the ironic multiplicity (geographic and temporal) of interwar Ukrainian Galicia: in arguing for the importance of Ukrainian cultural memory, the journal’s contributors spoke to the future citizens of an imagined nation that did not yet exist (Ukraine), within the boundaries of a historical territory that would never exist again (Galicia), governed by a country that had been erased and rebuilt, and would soon be erased and divided again (Poland). Meanwhile, Galicia, in its interwar multi-ethnic form, was about to be destroyed in the Holocaust and WWII, in ways that no one could anticipate.

Nova khata became one of the most popular magazines of Galicia. In its inaugural issue, its subtitle was “A Magazine Devoted to Fashion and Women’s Household Affairs,” later replaced with “A Magazine for Nurturing Domestic Culture.” The journal covered eclectic topics such as women in the West (Ellen Key and Dorothy Thompson), beloved Ukrainian writers of the past (Lesya Ukrainka, Ivan Franko), Montessori education, and “female psychology.” At the same time many of its pages were devoted to ordinary domestic reality, and it aimed to improve the everyday life of Ukrainian women by offering tips on interior design, table-settings, recipes, gardening, sewing, hygiene, cosmetics, and clothing.

|

|

The Folk Art Mission

Aside from serving as a women’s periodical, Nova khata had a clear mission to educate its readership about Ukrainian folk art, as well as to demonstrate the central role that women can play in the preservation and propagation of national handicrafts. This stems from the larger purpose of the Ukrainian Folk Art Cooperative, founded in Lviv in 1922: to teach courses and operate workshops in folk handicrafts, and to both exhibit and sell these goods locally and abroad.

This folk art revival harkens back to the Arts and Crafts movement and the interest in applied arts that spread throughout Europe. In both Ukraine and Russia in the early 1900s, this search for vernacular forms was associated with the “kustar” (peasant “handicraftsman” or artisan) revival movement: aristocrats and artists established rural folk art workshops where peasants could create artisanal crafts, such as the embroidery workshops at Verbovka and Skoptsy.

|

|

Yet, Ukrainian aspirations differed from similar movements in Russia and the West: along with other members of the Eastern European intelligentsia, Ukrainians were motivated not just by their fear that folk traditions were being destroyed by industrialization, but also by their desire to develop their national identity and assert the distinctiveness of their traditional culture when they were being repressed by powerful states. [2]

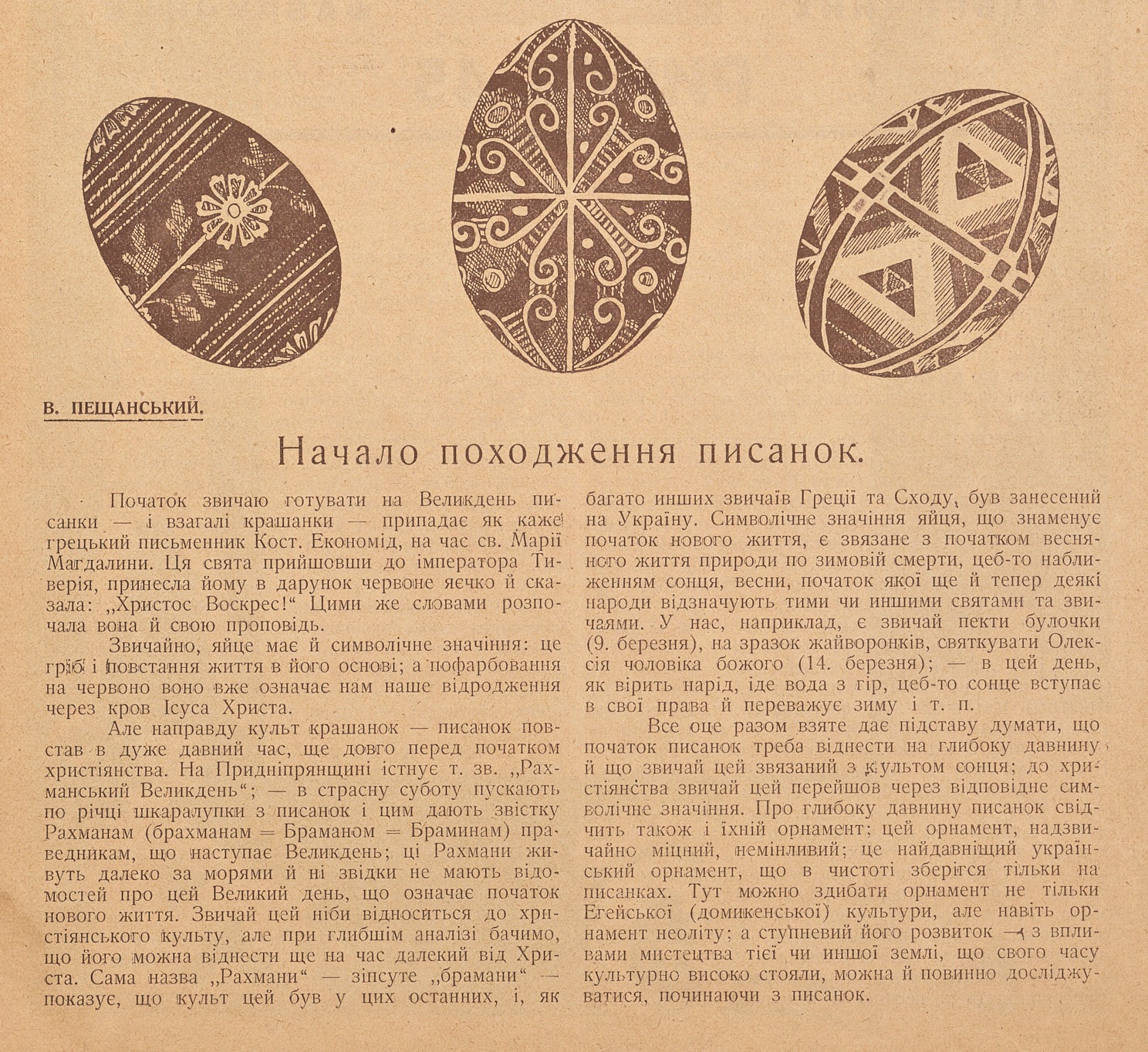

Combining this folk art mission with its other aim of enhancing domestic culture, Nova khata suggested Ukrainian traditions as a means to beautify one’s home, so as to be surrounded by objects evoking Ukrainian culture. The contributors thus instructed their readers how to create Ukrainian Easter eggs and Christmas ornaments, and how to embroider clothing and napkins with the colorful patterns of the Ukrainian tradition.

Women’s Sports, Hygiene, and Healthy “Body Culture”

Apart from advocating for the distinctiveness of Ukrainian culture, the editors also focused on internationally popular topics like health, outdoor exercise, and sports. This vogue evolved from the German body culture (Körperkultur) movements of the 19th- and early 20th-centuries, such as Lebensreform (Life-Reform) and Wandervogel (Wandering Bird), which called for people to exercise outdoors in the fresh air and cultivate healthy bodies through clothing reform, gymnastics, nudity, and natural food. These movements sought to counteract the effects of industrialization and urbanization, such as poor sanitation, but often had a political undercurrent, influencing all sides of the political spectrum. Social Democrat Franz Wildung summed it up in 1926: “Sport is a rebellion against the threat of decay, an expression of the will to live. Young life does not want to be crushed on the treadmill of the economic system.” Soviet “Hygienism” also influenced Slavic peoples of this era, especially Poles and Ukrainians. No less than Lenin himself viewed women’s physical fitness as a government priority: “It is our urgent task to draw women into sport.”

Echoing ideas found throughout Russia, Europe, and America, the editors of Nova khata put body culture and physical fitness at the forefront of the journal’s mission, as evidenced in articles, advertisements, and photographs, which urged women to participate in sports, wear less restrictive clothing, and pay greater attention to their health. In the photograph from Nova khata below, the young women in flowing white dresses are members of the “Sokol” (Falcon) gymnastics club in Lviv, a local outgrowth of the influential pan-Slavic Sokol movement, which promoted physical fitness, especially gymnastics. Founded in 19th-century Prague, it spread throughout the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Russia, and was very popular in interwar Poland.

Nameeta Mathur has pointed out that the emphasis on women’s sport and physical fitness in Poland was heightened by a “sports nationalism,” which led to a proliferation of new sports facilities for women, including in Lviv. Yet she aptly notes the contradiction between this call for women to be freer and more active, and the equally strong message that women must not give up their identities as mothers and wives, and that sportswomen must be feminine and attractive. This latter contradiction is well exemplified in the pages of Nova khata, which mingles articles on the benefits of sports with illustrations of glamorous women in fashionable swimsuits or tennis outfits.

Motherhood and Fashion

Motherhood, in fact, is glorified in the pages of Nova khata. The journal includes both practical tips on childrearing and a plethora of folk art-inspired children’s clothing, thus underscoring that women, however emancipated and athletic, should also fulfill their roles as both caregivers of children and preservers of national folk traditions. A special issue on motherhood in 1934 included articles on “Motherly Love” and “Mothers and Photography.” This celebration of motherhood also has deep roots in Slavic culture and folklore.

|

|

At the same time, the journal aimed to appeal to fun-loving female readers with illustrations of glamorous dancers and frivolous masked balls. It evoked the “New Woman” of the 1920s through fashionable flapper outfits, and proclaimed its modernity with pictures of women driving motorbikes and automobiles.

|

|

Conclusion

Today, as Ukrainian culture is greatly threatened by war, library collections can play an essential part in preserving its artifacts, not only of the present, but of previous decades that are little understood in the West. This new acquisition consists of 24 issues printed between 1925 and 1935, including several issues not available online. Rich with ideas that fascinated Europeans of the interwar era, Nova khata also puts a native stamp on these topics, situating them within Ukrainian traditions. This Galician journal thus gave voice to a Ukrainian perspective at a time when Ukrainians in both Poland and the Soviet Union lacked political power and independence.

Notes

[1] Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History, 51–56; Timothy Snyder, The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999, 140–53.

[2] Alison Hilton, “From Abramtsevo to Zakopane: Folk Art and National Ideals in Russia and Eastern Europe”; Katia Denysova, “From Folk Art to Abstraction: Ukrainian Embroidery as a Medium of Avant-Garde Experimentation”; Edyta Barucka, “Redefining Polishness: The Revival of Crafts in Galicia around 1900.”

Featured image: Nova khata 5, no. 12 (1929). Cover illustration by Mykola Butovych (1895–1961).

Date

November 22, 2023